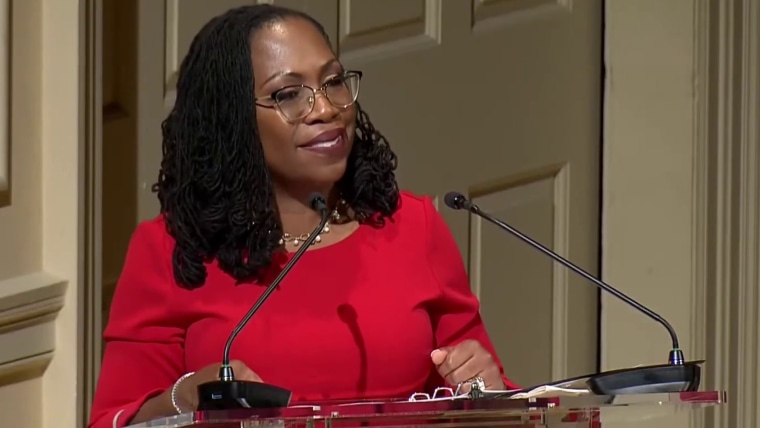

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson has made it clear in her first days on the Supreme Court that she is not just any new justice. She is a justice who is ready to do what needs to be done.

I have followed the court closely for most of my life. I remember asking to keep the TV on during dinner to watch Clarence Thomas’ confirmation vote in 1991. I was in middle school. I have closely followed or covered the first terms of the seven other justices, all of whom took the bench after I graduated from law school in 2005.

I have never seen a justice begin a career on the high court in the manner we are seeing from Jackson.

In all that time, I have never seen a justice begin a career on the high court in the manner we are seeing from Jackson.

Most new justices take a bit of time before they start to really get up to speed. Even if their votes matter, new justices generally take a while before their presences are really felt on the court. As I wrote Monday, though, the court’s current makeup — and the cases the justices are scheduled to hear — could lead Jackson on a different path.

Thus far, she has taken that different path.

From the first oral argument Monday, in a Clean Water Act case, Jackson was participating fully — raising significant questions about the meaning of “adjacency” and engaging in back-and-forth discussions with the lawyers appearing before the court.

It was on Tuesday, though, in a Voting Rights Act challenge to Alabama’s proposed redistricting maps, which a lower federal court found violated Section 2 of the law by diluting Black voters’ influence, that Jackson left her first real mark on the court.

Despite the Voting Rights Act’s status as “one of the great achievements of American democracy,” as Justice Elena Kagan described it Tuesday, “in recent years, this statute has fared not well in this court.” Kagan went on to lay out how the court has chipped away at the Voting Rights Act and its protections since Chief Justice John Roberts — a longtime skeptic of the law — joined the court. Detailing the ways Alabama’s arguments in Tuesday’s case would pare it even further, she asked the state’s lawyer, almost rhetorically, “So what’s left?”

It was a strong statement for a sitting justice to make about the decisions of her colleagues over the past decade.

The justice’s evidence was fact. But this line of argument has been all but cut out of legal debate in recent decades.

A few minutes later, Jackson took things a step further, not just questioning the court’s recent decisions, but opening a line of reasoning — and reality — that has been missing from the court’s discussions altogether for decades.

“I don't think we can assume that just because race is taken into account that that necessarily creates an equal protection problem,” Jackson told Alabama Solicitor General Edmund LaCour Jr. — and, just as likely, the justices alongside her.

This was not a standalone point. It was a windup to a dismissal of an entire motivating principle of the conservative legal (and, at times, political) movement. It was what I imagine is just the beginning of Jackson’s argument — on conservatives’ own ground of “history and traditions” — against “race-neutral” constitutional standards in a nation (and world) of regular, systemic and extreme examples of racism.

Referring to the “history and traditions” standard — so often invoked by Thomas and others using some version of originalism or “original intent” as their means of constitutional interpretation — Jackson said, “[W]hen I drilled down to that level of analysis, it became clear to me that the framers themselves adopted the equal protection clause, the Fourteenth Amendment, the Fifteenth Amendment, in a race-conscious way.”

The amendments and legislation at the time, she explained, were devised to help ensure that recently freed slaves were “actually brought equal to everyone else in the society.” She buttressed this by citing and quoting from “the report that was submitted by the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, which drafted the Fourteenth Amendment.”

Then Jackson, the first Black female justice, quoted the lawmaker who introduced the Fourteenth Amendment as saying of its purpose: "[U]nless the Constitution should restrain them, those states will all, I fear, keep up this discrimination and crush to death the hated freedmen."

Jackson then concisely brought us to her point. “That's not a race-neutral or race-blind idea,” she told LaCour, her colleagues, the room and the country of this original purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment. The justice’s evidence was not news to historians or others who study the Civil War era and the post-Civil War amendments. It was fact. But this line of argument has been all but cut out of legal debate in recent decades.

“[S]he is correct as a matter of fact and history,” Adam Serwer wrote. “[I]t's just not something you hear a justice say.”

Until you do.

As Rep. Ayanna Pressley, D-Mass., told me in February about the importance of President Joe Biden’s pledge to name a Black woman to the court, “[W]hat I know is that when Black women are at the table, we shake the table, and I don’t mean physically, I mean because we call into account different questions.”

Often in Biden’s tenure, we have heard pundits and others raise the question of whether Biden is “up to this moment” or something similar.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson has been on the Supreme Court for only a few months, and she has sat on the bench for only four oral arguments thus far, but it is already clear that no one is going to be asking that question of her. What’s more, it is entirely possible that Biden’s nomination of Jackson might well be one of his most “up to this moment” contributions to history.